Truman State University’s Department of Public Safety had officers participate in a crisis intervention training workshop to deal better with mental health situations on campus.

Sara Holzmeier, Director of Public Safety at Truman State, explains that in the last six months, she’s been working with a committee to form a Crisis Intervention Team, or CIT, focusing on de-escalation tactics. De-escalation is a tactic used to try and keep people from harming others or themselves in life-threatening situations.

“The Crisis Intervention Team concept basically brings together law enforcement, hospitals, mental health providers, and counseling in the community,” says Holzmeier.

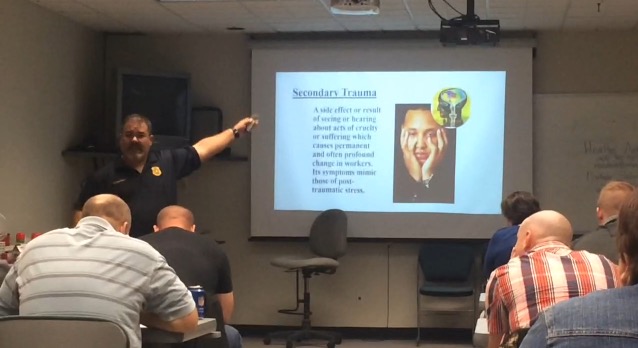

The program’s 40-hour curriculum covers a number of topics such as verbal de-escalation tactics, suicide by cop and a variety of other issues. The course features several interactive exercises, including a de-escalation role-play, and “lived experiences,” in which a panel of people who’ve been diagnosed with mental health disorders talk about their illnesses and any interactions with law enforcement.

Holzmeier says the federal and state governments have continued to cut mental health funding through the years, while police officers have seen an increase in calls related to such issues.

“Truman’s not an easy college, and not only are people out on their own for the first time, but they’re dealing with life stress, they’re dealing with academic stress, and their mental health and well-being sometimes people push to the side,” says Holzmeier. “We do deal with a lot of depression and anxiety and other issues that the Truman students have, so it’s been very helpful for us to get trained in this.”

Prior to the introduction of CIT training in law enforcement, Holzmeier says officers received little, if any, training regarding mental health. They would receive some verbal de-escalation training on how to interact with people, but nothing specifically concerning mental health situations.

Brenda Higgins, director of Truman State Counseling Services, says it’s crucial for officers to be able to distinguish a mental health issue from a legal issue, as each should be handled differently.

By the end of October, Higgins says every campus and city police officer in Kirksville will have been CIT trained. The Department of Public Safety also has a crisis trainer on staff, who they can call on to deal with people in crisis situations.

Although CIT was originally developed in Memphis in 1988, it has only recently begun to catch on and spread throughout the country.

Sergeant Jeremy Romo, coordinator of the Missouri State Crisis Intervention Team, says that although the program is growing, it has not yet penetrated many rural areas, being primarily adopted by urban police departments.

However, Romo says he believes Missouri is one of the leaders in CIT, with it now being implemented by many rural police departments in the state.

An essential aspect of Romo’s job as coordinator involves traveling throughout Missouri to educate officers on the importance of mental health training. He says about 75 percent of the state has moved in the right direction so far, but he hopes eventually every city in Missouri will adopt the program.