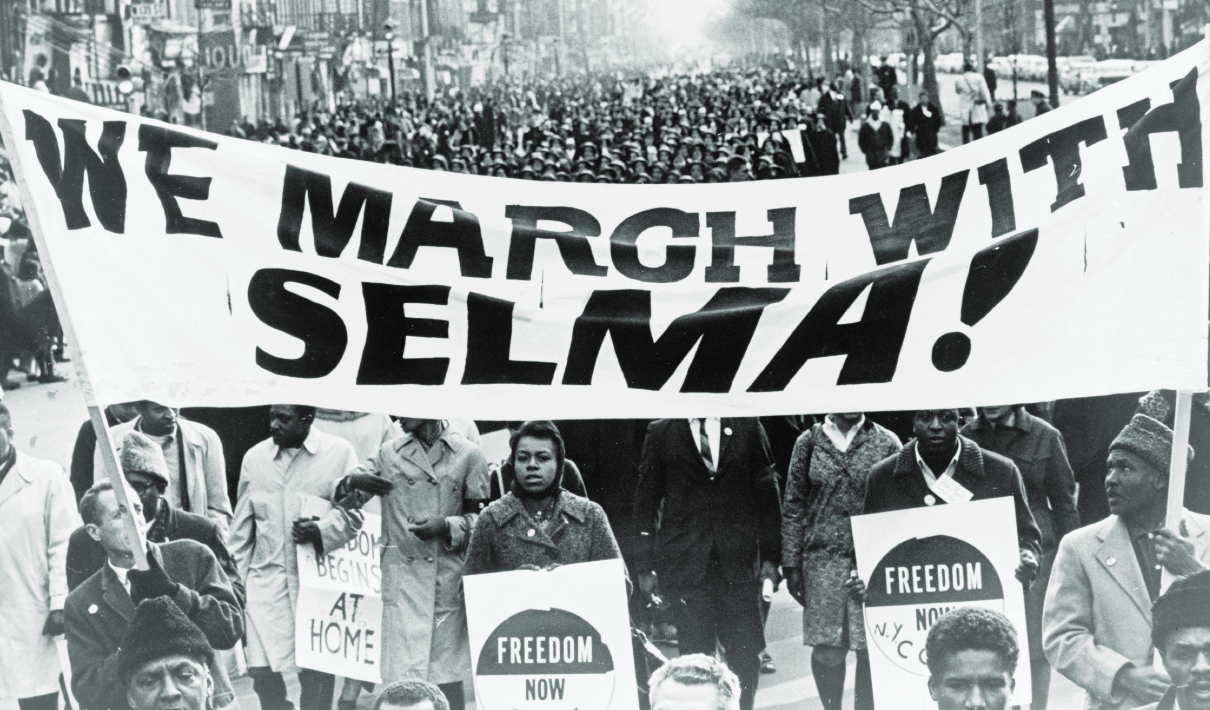

“[T]hey called us names and told us to return. And when we didn’t, they charged as if they were a cavalry in a battle or in a war.”

This recollection from alumnus Alphonso Jackson, former U.S. secretary of housing and urban development, is from his experience during the attempted march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, Alabama, by civil rights activists March 7, 1965. The day later became known as “Bloody Sunday,” because Alabama state troopers forcibly blocked then attacked peaceful protesters at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Jackson will speak at Truman State March 30 following a viewing of the 2014 motion picture “Selma” in Baldwin Auditorium.

The film puts viewers inside this historical account, stepping into the home of Martin Luther King Jr., through the hidden door in the wall of Lyndon B. Johnson’s Oval Office and into the shoes of Annie Lee Cooper as she tries to register to vote.

It also brings to life faces and names most students have seen in American history textbooks — Malcom X, Coretta Scott King, Congressman John Lewis and countless others. Viewers journey across them Edmund Pettus Bridge, see the wall of Alabama State troopers, and experience the panic amid fleeing people and unleashed brutality. Viewers also will see the struggle behind the scenes, and finally on the road to Montgomery, to gain African Americans the right to vote.

Jackson said one of the main things he wants to emphasize to attendees is the movie, while a good attempt at representation and raising awareness of what happened on the road to Montgomery, is not totally accurate. He said several key players who were extremely influential were not given substantial time or attention throughout the film. Jackson said these included Rev. C.T. Vivian, who helped arrange for King to come to Selma, and Bernard Lee, King’s top aide at the time and the man who recruited Jackson to help with voter registration in Alabama.

Jackson said during 1965 he was a freshman at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania when Lee arrived and convinced young men from the nation’s first degree-granting historically black college and university to make the trip to Selma that March.

“I felt extremely compelled to go, because I think in many ways, even though I was low income, I had privileges that many of my brothers and sisters in Alabama did not have,” Jackson said.

Jackson said he recalls gathering with others the morning of March 7, 1965. He said the group marched to a local church then proceeded toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge spanning the Alabama River.

Jackson described the minutes leading up to the attacks, when the protesters arrived to find the other side of the bridge blocked by Alabama state troopers.

Jackson said the police force also had deputized many white males in Selma, so shuffling up to the bridge, the protesters faced law enforcement and disgruntled residents determined to stop the march from continuing. Jackson said he was standing about nine rows back from the front of the line when the state troopers and deputized Selma citizens, hearing the crowd’s refusal to end the march, began to attack the assembled protesters.

“It was a very, very tremendous blow at that point in time because they started moving back, the horses started coming at us,” Jackson said. “It was not a very pretty sight, but it didn’t deter me from doing what I thought was right.”

For more information, pick up a copy of this week’s Index or read online on Issuu.